NYC Accelerator PACE Financing

Background

CastleGreen Finance is pleased to announce the closing of One Park Road, West Hartford, CT, a $13,767,000 Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE) transaction. In partnership with Lexington Partners LLC, the property developer, and the Connecticut Green Bank, the program administrator for the state of Connecticut C-PACE program, CastleGreen Finance is delighted to be part of the largest C-PACE transaction to date in Connecticut.

Project Overview

For 135 years, the Sisters of St. Joseph of Chambéry have occupied a convent on Park Road in West Hartford, Connecticut. One Park Road is the redevelopment of this iconic property which will add a 292-unit multi-family housing complex on the 22-acre property while maintaining much of the greenspace and preserving the Sisters’ history and ensuring their retirement security at the property.

A new 230,000 square foot four-story building over a one-story parking deck, will be connected to the existing structures and is designed to look like a series of separate buildings while providing a neighborhood feel.

One wing of the historic convent will continue to be owned and occupied by the Sisters. The remaining 111,000 square feet of the Colonial Revival-style convent is undergoing renovation into a mix of studio, one-, two- and three-bedroom apartments.

The long-discussed redevelopment of this iconic property is the result of the partnership between the Sisters of St. Joseph, Lexington Partners, and the Town of West Hartford, and it will bring new rental housing to the fast-growing Park Road/West Hartford area. Construction on the $70 million project is scheduled to begin in mid-2021, with completion expected in the spring/summer of 2023.

CastleGreen Finance has facilitated approval of the $13.7 million C-PACE project through the Connecticut Green Bank’s C-PACE program. The project provides the project developer with access to affordable, long term financing for qualifying clean energy and energy efficiency upgrades that lower energy costs.

Martin J. Kenny, president of Lexington Partners, states, “We feel the Park Road business district is to West Hartford as Brooklyn is to New York City. The project will serve to strengthen the Park Road business district and provide a gateway to and combine with what is going on in Parkville. We needed creative financing in our capital stack to help bring this project to fruition. The CastleGreen team presented a compelling financing solution and delivered on time and as promised.”

C-PACE financing of clean, sustainable energy efficiency projects embraces the collaboration of public/private financing of energy improvements for the redevelopment of this iconic property.

Sal Tarsia, Managing Partner of CastleGreen Finance states, “Lexington Partners is a key player in the revitalization of the Park Road business district, creatively utilizing C-PACE financing for its ESG initiatives. It was a pleasure working with the Lexington team on a redevelopment which exemplifies the original purpose of what C-PACE was created for, but also respects and preserves the history of the property.”

“We are excited to see CastleGreen Finance closing their first project in Connecticut; the largest C-PACE project to date, in the state. This project is an excellent example of private capital working in the state’s open market for C-PACE financing,” said Bryan Garcia, President and CEO of Connecticut Green Bank. “The redevelopment at the Sisters of St. Joseph’s convent will not only make energy usage at the property more efficient and affordable, it will create housing opportunities and continue to support the Sisters, who strive to serve all people, especially those in need. This project will make a positive impact in West Hartford and exemplifies the Green Bank’s vision of a planet protected by the love of humanity.”

About CastleGreen Finance – www.CastleGreenfinance.com

CastleGreen Finance, in partnership with X-Caliber Capital, is a private capital source focused on Commercial PACE (Property Assessed Clean Energy) financing. CastleGreen Finance brings extensive experience in commercial real estate across a broad range of financial disciplines. The extensive real estate experience of the CastleGreen team, combined with its core C-PACE capabilities, provides our clients with the knowledge and resources to create a superior capital stack that meets all its needs and helps to unlock the potential of their commercial real estate. We understand that the most important part of any real estate transaction is showing up with the capital at closing. Our team focuses on the details of every deal to ensure we can get our clients to the finish line.

Version 1.0 – June 1, 20121

OVERVIEW: …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3

PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 2.1. Eligible Improvements…………………………………………………………………………………………………..4

TRANSACTION PROCESS……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7

FEE STRUCTURE ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 HANDBOOK DOES NOT REPRESENT LEGAL ADVICE…………………………………………………………….. 9 CONTACT INFORMATION …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 EXHIBITS: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 10 EXHIBIT A……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 11 Form of Assessment Contract ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 EXHIBIT B………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………12 List of Current Administrative Fees as of June 1, 2021 ………………………………………………………….. 12

The CastleGreen C-PACE program (the “Program”) is administered by CastleGreen Services, LLC (“CGS” or the “Administrator”) under a program sponsored by the California Statewide Communities Development Authority (the “Authority” or “CSCDA”), a joint powers authority. The Authority administers a commercial property assessed clean energy (“C-PACE”) program (the “Open PACE Program”) under the California PACE Legislation, Division 7, Chapter 29 of the California Streets & Highways Code.

The Authority is offering the Open PACE Program on a statewide basis to encourage the installation of distributed generation renewable energy sources, energy efficiency improvements, water efficiency improvements, seismic strengthening improvements and electric vehicle charging infrastructures (collectively “C-PACE Improvements”).

The Program allows commercial property owners to obtain long-term financing for eligible PACE improvements from proceeds derived from the sale of the bonds and other financing mechanisms authorized by law. It utilizes a tool that is widely used by local agencies in California to finance public benefit projects: land-secured financing. State law has long provided cities and counties with the power to issue bonds and levy assessments on the county property tax bill to finance public projects such as sewers, parks, and the undergrounding of utilities. Chapter 29 of the Improvement Act of 1911, commencing with Section 5898.10 of the Streets & Highways Code of the State, authorizes the levy of contractual assessments to finance the installation of C-PACE-eligible improvements. The assessment contract (“Assessment Contract”) is voluntary and is executed by each participating property owner and the Authority.

Under the Program, a contractual assessment lien is placed on each participating property in an amount necessary to (i) finance the installation of the PACE Improvements over a 5-39 year period, depending upon the expected useful life of the financed improvements, (ii) pay for costs of issuing bonds or other financing mechanisms and (iii) pay the costs of administering the Program. The contractual assessment installments are collected on the property tax bill of the county in which the participating property is located, and the funds are used to repay the PACE financing. If the owner sells the property, the contractual assessment obligation remains an obligation of the property.

Under the Open PACE Program, if a property owner fails to pay the annual contractual assessment installments, CSCDA is obligated to strip the delinquent installments off the property tax bill and commence judicial proceedings to foreclose the lien of the delinquent installments.

CSCDA has engaged third-party administrators, including CGS, to administer its Open PACE Program. CGS will review and process applications, register contractors, interact with third-party capital providers/lenders, and provide services to property owners who wish to participate in the Program. The Authority allows for financing mechanisms that include the issuance of assessment-backed bonds. The bonds are issued under an indenture between the Authority and a trustee for the holders of the bonds. The capital to fund improvements is provided through the purchase of bonds or other financing mechanisms and will be provided by an affiliate of the Administrator or a third-party capital provider.

C-PACE financing has several positive features that are attractive to property owners, including: Long duration, fixed rate financing. The availability of interest-only periods, provided that the bond will fully amortize by its maturity date.

2.1. Eligible Improvements

As permitted by California’s PACE legislation, the Program allows qualifying property owners to finance certain improvements to their commercial property.

Improvements are generally broken down into three categories, collectively described as the “Improvements” as noted previously:

c) Resiliency

In accordance with the Program, minimum energy efficiency specifications are set at EnergyStar, California Title 24 and Title 20, and WaterSense standards, as applicable. Efficiency standards will “ratchet-up” with EnergyStar, WaterSense, California Title 24 and Title 20 standards, or other new standards as may be appropriate and as agreed upon by the Administrator. Eligible improvements will be verified in advance of closing as eligible under the California PACE legislation by the Administrator.

Any solar PV system must be eligible for and participate in California Solar Initiative or an equivalent utility rebate program, unless the property is not connected to the electricity grid or such utility rebate program is not available.

To qualify under the Program, all proposed improvements must be affixed to a building or facility that is part of the subject property and constitute an Improvement.

Subject to the exceptions noted in Section 2.2, the Program will finance new construction, deep retrofits, “gut rehabilitations”, or minor/moderate renovation projects. Improvements which have already been installed (or partially installed) may be eligible for Program financing on a case-by-case basis however in no instance shall this lookback period extend for more than 39 months from installation date (as determined by the Certificate of Occupancy or other documentation approved by the Administrator).

The Administrator reserves the right to impose additional qualifications on certain Improvements. This may include the acquisition of additional technical information, operational or maintenance information, or information regarding the nature of the ownership or permanent affixation to the real property.

The Administrator does not recommend or endorse any specific Improvement and participation in the Program does not constitute an endorsement, or provide any form of guaranty or warranty, with respect to eligible Improvements.

2.1.1. Energy and Water Conservation and Efficiency Improvements

Qualifying conservation and efficiency improvements are measures which reduce consumption through conservation or a more efficient use of water, electricity, natural gas, propane, or other forms of energy. Examples include (but are not limited to):

Seismic strengthening – a broad array of improvements and measures designed to prevent damage or destruction of a building during a seismic event.

Wildfire hardening – any improvements approved by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. (https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=SHC§i onNum=5899.4.)

Properties/Property Owners

To qualify for financing under the Program, a property and property owner must meet the following eligibility criteria:

• The property must be located within the geographic boundaries of a local government who has opted into the Program.

o For a list of current eligible local governments please see CSCDA’s Open PACE website at https://cscda.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Agency-List- 5.7.21.pdf.

• The property must be a commercial property, which is defined as (i) a property not designed for residential use; or (ii) designed for residential use, of five or more non- owner-occupied units; for projects financing new construction of a residential building containing five or more units, the initial construction must be undertaken by the intended owner or occupant.

o Depending on the legal structure and proposed scope of improvements, condominium properties, co-op ownership groups, properties subject to long- term ground leases, and properties subject to homeowner associations may be eligible on a case-by-case basis.

o property taxes for the property must be current,

o any property-based debt must not be subject to any notices of default or other

evidence of debt delinquency,

o the combined mortgage debt and C-PACE assessments may not exceed 95% of

the market value of the property,

o the property must not be subject to any involuntary liens, judgments or defaults

or judgments in excess of $5,000, unless such liens shall be satisfied to the

satisfaction of the Administrator with the proceeds of the financing at closing.

o the property owner must not currently be in bankruptcy or have declared bankruptcy within a period of ninety days prior to the anticipated closing date of the financing.

The Administrator reserves the right to impose additional eligibility qualifications on certain properties or owners, in its sole discretion.

2.3. Installation of Improvements/Contractor Registration

The Improvements must be installed by a contractor that is registered with the Program; however, the property owner may also install his/her own Improvements and will not need to be registered. If the financing is for Improvements for which construction or installation of is complete such that the Improvements have been fully installed on the property, there is no need for the contractor to be registered with the Program.

A full list of contractors that have registered with the Program may be obtained from the Administrator and may also be found on its website. Contractors are any general contractor who has been engaged by the property owner to install the Improvements who shall provide the Administrator the following:

a) An executed Contractor Registration Agreement, as provided by the Administrator,

b) All licenses, certifications as required by the State or local Jurisdiction where the improvements are being Installed.

1 Market value may be determined by the Administrator, in its sole discretion, using one of the following methodologies: a) an automated valuation model (“AVM) prepared by an independent third-party, a broker price opinion or an independent appraisal performed by a licensed, independent appraiser.

c) Any additional information as requested by the Administrator from time to time.

Registration of a contractor with the Program is neither a recommendation of such contractor nor a guaranty of or acceptance of responsibility for such contractors by CSCDA, the Administrator, or the County or City where the property is located upon which the Improvements are installed.

2.4. Lender Consent/Underwriting Requirements

If a property is secured by a mortgage or other form of recorded debt, it is a requirement of the Administrator that, prior to entering into an Assessment Contract, the property owner must provide notice to and receive the written consent of any holders or loan servicers of any existing mortgages on the property.

Generally, the investor or purchaser of the bonds issued by the Authority, will perform its own underwriting in addition to the underwriting of the Administrator and the investor may have underwriting requirements more stringent than those of the Program.

3. TRANSACTION PROCESS

3.1. Financing Structure

The Authority will finance the installation of Eligible Products by issuing bonds backed by the assessments created by the Program. The proceeds from the sale of the bonds will provide capital to finance the Improvements. The term of the assessment may not exceed the useful life of the Improvements, as determined by the Administrator in its sole discretion based upon information provided by any energy reviewers/auditors or industry information provided.

3.2. Inquiry

A property owner may apply with the Program for C-PACE financing by completing and submitting an Inquiry form to: inquiry@CastleGreenfinance.com. Please find the Inquiry form at: CastlegreenFinance.com/CA Program. The Administrator shall review and request any further information it needs to evaluate the project. The Administrator will approve or deny the Inquiry, via email to the applicant, on a timely basis.

3.3. Term Sheet

After preliminary approval is granted by the Administrator a term sheet will be issued by an affiliate of the Administrator or a third-party capital provider. The term sheet will outline the terms of the proposed transaction under the Program, as well as any conditions precedent to closing. If the property owner elects to execute the term sheet (subject to any negotiated terms and conditions) the project will proceed and the property owner will work with the capital provider and the Program to begin the underwriting process.

3.4. Underwriting

During the underwriting process, the capital provider will work with the Administrator to obtain all due diligence items it requires for closing. As discussed previously, capital providers may require more information on a project than what is required under the Program by the Administrator. The Administrator will coordinate for the receipt of diligence information with the property owner and the capital provider.

3.5. Documentation

Through its participation in the Open PACE Program, the Program has worked with the Authority to assemble a package of closing documents that will be used to evidence the terms and structure of

the financing as well as the form of assessment that will be levied at closing. These documents satisfy all requirements of the Authority and the capital provider. The property owner and its counsel will review these documents and coordinate throughout the process with the Administrator and the capital provider.

3.6. Closing

Upon finalization of the documents referenced above, the Administrator will coordinate the process whereby the Assessment Contracts will be recorded in the land records of the applicable jurisdiction in which the property is located. After confirmation of recording is received, the Administrator will coordinate the closing based on the date agreed with the property owner in the Assessment Contract.

The Assessment Contract is comprised of the following amounts:

3.7. Disbursements

Unless the Project funds have been fully disbursed to the property owner on the closing date, the remaining Project Costs will be disbursed to the property owner, from time to time, according to an agreement between the capital provider, and the property owner. Disbursement requests shall be prepared by the capital provider (or its designee) and shall pertain directly to the installation of the eligible Improvements. Documentation may be required by the Administrator (in coordination with the capital provider) to evidence the expenses.

After receipt of a disbursement request (and any requested supporting documentation), the Administrator will authorize and instruct the trustee to release the requested funds be sent to the property owner or its contractor within a commercially reasonable period of time.

Once the Improvements have been fully installed, the property owner will submit a final disbursement request (such final disbursement request to serve as a form of completion certificate) to the Administrator certifying that the installation of the eligible improvements have been completed and that the Improvements are operating as designed and intended.

3.8. Assessment Repayment

Repayment of the C-PACE assessment is subject to the terms and conditions of the transaction documents which evidence the assessment. The Assessment represents a non-ad valorem tax on the property tax bill issued by the applicable County’s taxing authority.

If an assessment installment payment, is not received by the date specified on the property tax bill, the Authority has the right to have such delinquent installment, and its associated penalties and interest, stripped off the secured property tax roll and immediately enforced through a judicial foreclosure action that could result in a sale of the Property for the payment of the delinquent installments, associated penalties and interest, and all costs of suit, including attorneys’ fees.

Prepayment of the assessment shall be either in full or in part as documented in the agreements. Any notice to the Administrator prior to the prepayment or any prepayment premium (if any) which may be due shall be documented in the agreements.

4. FEE STRUCTURE

All fees for participation in the Program are detailed in Exhibit B. These fees may be reduced, increased, waived, or modified at any time, and for any transaction, at the sole discretion of the Administrator. Modification of fees payable to the Authority require approval by the Board of Directors of the Administrator prior to any modification.

Fees payable to a jurisdictional tax collecting authority may be reduced, increased, waived, or modified by that tax collecting authority as applicable.

5. HANDBOOK DOES NOT REPRESENT LEGAL ADVICE

The Administrator does not provide legal, financial, taxation, or accounting advice to any prospective property owner. No statements or representations, either in this Handbook or made as part of the transaction process, should be construed as such advice. Property owners are strongly encouraged to seek the advice of competent professionals as part of participating in the Program.

6. CONTACT INFORMATION

If you have any questions about the Program, this Handbook, or the Administrator, please contact the Administrator:

CastleGreen Services, LLC, 3 West Main Street, Suite 103, Irvington NY 10533 e-mail: inquiry@castlegreenservices.com

website: castlegreenfinance.com/CAOpenPace

7. EXHIBITS:

Exhibit A – Form of Financing Application Exhibit B – Program Fees

EXHIBIT A

Form of Assessment Contract

11

EXHIBIT B

List of Current Administrative Fees as of June 1, 2021

Fees at Transaction Close*

Services

Provider

Fee

| Program Administration Construction Management Asset Servicing Recordation | Administrator | Base Program Fees: 1% for Assessments over $1,000,000 Construction Asset Management Services: $500 per disbursement request Asset Servicing: Assessments between: $1,000,000 to $10,000,000: $10,000,000 to $25,000,000: $25,000,000 + Lien Recordation: Between $150-$200 per parcel 0.25% (25bps) 0.15% (15bps) 0.10% (10bps) Additional Fees (if applicable): For transaction related services including but not limited to: Document customization Underwriting support Fees will be confirmed prior to providing such services. |

| Bond Counsel and Legal Opinion | Orrick | Standard Project Fees: Bond amounts: Up to $750,000 $750,000 – $1,125,000 $1,125,000 – $1,650,000 $1,650,000 – $2,360,000 $2,360,000 + 0.75% (75bps) ($3,500 minimum) $5,625 0.50% (50bps) $8,250 0.35% (35bps) Additional fees may apply for services beyond Standard Project Fees – such as involving counsel in property owner negotiations, revisions to Program Documents, or drafting/reviewing documents which are deemed to be outside the standard closing process. |

Authority Administration

Trustee Trustee Legal

Authority

Wilmington Trust Wilmington Trust

0.75% (75bps)

Calculated based on Project Costs and subject to a minimum fee of

$10,000 and a maximum of $250,000

TBD: Estimate $3,250 per bond/Assessment Contract as applicable $1,200 per bond

| Tax Administrator | DTA | Calculated on Project Costs: Up to $1,000,000 $1,000,000 – $5,000,000 | 0.52% (52 bps) $5,200 for the first $1MM of Project Costs, plus 0.10% (10bps) of Project Costs thereafter, up to $5MM |

12

Over $5,000,000 $9,200 for the first $5MM of Project Costs, plus 0.025% (2.5bps) of

Project Costs thereafter *Unless otherwise noted all Fees will be calculated on the outstanding Assessment amount.

Bond Issuance CDIAC .025% (2.5bps) Fee

Services Trustee

Tax Roll Administration

Court Collection Fee

Provider Wilmington Trust

DTA

Local County Government

Annual Fees

Fee $1,825 per bond issuance

$50 per parcel enrolled

TBD: $500 – $1,100 per County (varies by the total number of parcels enrolled in the County)

Varies by County

13

June 30, 2020

Despite the ongoing impact of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) on the U.S. economy and on borrowers’ ability and willingness to repay outstanding debts, DBRS Morningstar’s outlook on the commercial property assessed clean energy (C-PACE) asset-backed securities (ABS) sector is stable. The coronavirus pandemic has had a limited effect on the C-PACE sector to date. With the closure of many nonessential businesses across the U.S., jobless claims have exceeded 47 million since mid-March, severely disrupting overall economic activity. We expect portfolios with exposure to hotel and retail properties to be the most negatively affected. Nonetheless, we expect limited credit deterioration in C-PACE securitizations due to the seniority of amortizing PACE assessments and underlying low loan-to-value (LTVs) ratios .

By providing short-term financial assistance, in the form of loans or grants related to the pandemic, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act has alleviated some economic difficulties on borrowers experiencing hardship—including consumers, small businesses, and large corporations.While we expect more pronounced performance deterioration in higher credit risk portfolios, the structural features and protections in typical C-PACE transactions will likely help mitigate the effect of deteriorating borrower credit. However, the uncertain magnitude of the economic impact related to the coronavirus may exert differing degrees of downward pressure on certain subordinate tranches.

In the context of this highly uncertain environment and in the interest of transparency, we revised our set of forward-looking macro-economic scenarios for select economies related to the coronavirus in the commentary Global Macroeconomic Scenarios: June Update, published on June 1, 2020. In our rating analysis, the moderate scenario is serving as the primary anchor for current ratings, while the adverse scenario serves as a benchmark for sensitivity analysis. This moderate scenario primarily considers two economic measures: declining gross domestic product (GDP) growth and increased unemployment levels. For asset classes where commercial-based obligors are the source of cash flows to repay the rated transaction, among other things, GDP provides the basis for measuring performance expectations.

Key highlights for the U.S. C-PACE and Single Asset Single Borrower (SASB) C-PACE asset classes include:

For more information, please see our commentary Global Macroeconomic Scenarios: Application to DBRS Morningstar Credit Ratings, published April 22, 2020.

by Patrick Dolan (US) and Ryan Graham (US) — September 7, 2020

To promote growth of renewable energy projects, the New York State Legislature recently passed bill A.7805/S.6523 (the “C-PACE Bill”), which will allow real estate developers and commercial property owners to obtain Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE) financing for new construction projects. C-PACE programs are thought to be beneficial for cities, promoting energy efficiency, reducing energy costs and promoting local economic development.

Generally, PACE financing is an attractive financing option that allows property owners to obtain funds from pre-qualified private lenders for energy efficient building improvements. PACE programs are administered by state government policies that classify certain clean energy upgrades as public benefits.

New York’s Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (“C-PACE”) program is administered by the Energy Improvement Corporation (“EIC”), a state agency, and dates back to 2009. The program was updated in 2019 to allow commercial property owners the ability to access third-party financing on favorable terms. For more information on the C-PACE program as previously administered in New York, refer to our News Wire update from August 2019.

Prior to the passage of C-PACE Bill, C-PACE financing was available only to finance improvements to already existing buildings. Under the new bill, the C-PACE program has been expanded to allow C-PACE financing for new construction projects. In passing the C-PACE Bill, the New York State Assembly emphasized that commercial real estate developers often fail to use the newest and most energy efficient equipment in new construction projects, because they could not take advantage of C-PACE financing. By saving 0n construction costs, real estate developers have gradually passed costs on to local communities via higher energy costs, emissions and pollution. In updating New York’s C-PACE program, the New York State Legislature hopes that real estate developers will be able to incorporate more energy-efficient equipment in new construction projects and mitigate future direct and indirect costs to local communities.

Industry advocates have widely applauded the New York State Legislature for passing C-PACE Bill. In particular, industry advocates have emphasized that the C-PACE Bill will benefit the New York economy that has been greatly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic downturn, and they hope that the C-PACE Bill will lead to an increase in investment and provide more work for construction workers, engineers and architects.

Governor Cuomo is expected to sign the C-PACE Bill in the coming weeks. The text of the C-Pace Bill can be found here. For regular reports on new developments affecting energy efficiency and clean energy, subscribe to the Norton Rose Fulbright Project Finance News Wire here.

by Adam Aton, Jean Chemnick, E&E News on November 14, 2020

From the Pentagon to the General Services Administration, President-elect Joe Biden has embedded climate-minded officials throughout his sprawling transition team. Climate experts, former Obama administration officials and green activists abound among the teams managing the transition for EPA; the Energy, Interior and Agriculture departments; and the White House Council on Environmental Quality. Unlike past transitions, officials with significant climate or clean energy experience also popup in departments like State, Defense, Treasury and Justice.

They’re even handling the transition at agencies that, so far, have been on the periphery of climate policy, like the Small Business Administration and the Federal Reserve. Of Biden’s 39 agency review teams, at least 19 have one or more officials with some climate background. Perhaps just as telling, many of the transition officials had a hand in the 2009 stimulus, to date the largest government investment in clean energy and the model for Biden’s climate plan. The teams include a cross section of union representatives, progressive policy experts, establishment loyalists, activist scholars, corporate envoys and technocrats.

It’s the latest test of the Biden team’s balancing act between progressives, whom it courted during the campaign, and the establishment veterans who have proliferated in the former vice president’s orbit for years. In the short term, some of the Biden transition’s biggest challenges will come from simply restaffing and rebuilding the agencies that were deconstructed under President Trump, said Aaron Weiss of the Center for Western Priorities. “These folks are going to be coming into departments that have, in many cases, been eviscerated,” he said, pointing to the exodus of scientists and career staffers from the federal government over the past four years.

EPA, for example, shed more than 700 scientists under Trump and had only filled about 350 of those positions as of January, according to a Washington Post analysis. “The amount of rebuilding that will need to be done is unprecedented,” Weiss said. The exit of so much essential staff over the last four years presents a challenge, said Tim Profeta, director of Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions. “But it’s also an opportunity in terms of recruiting new, motivated talented civil servants who would be dedicated to the mission of addressing climate change in the federal government,” he said.

Profeta helped lead the Climate 21 Project, or C21, which yesterday unveiled 300 pages of recommendations for a new administration to prepare for a full-court press on climate change (Greenwire, Nov. 11). The group’s suggestions cover 11 government offices, agencies and departments from the Office of Management and Budget to EPA to the State Department. It also calls for a new White House policy council to oversee work on climate across the federal agencies. The C21 plan was written in part by members of Biden’s transition team.

One is Joseph Goffman, serving on the EPA transition. He was EPA’s top lawyer on climate and air issues in the Obama administration, and he played a leading role in crafting the Clean Power Plan and regulations for methane from oil and gas operations. Another is Robert Bonnie, leading the transition at USDA. Bonnie was climate adviser to Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack—himself a close Biden ally—and later served as the department’s undersecretary for natural resources and environment. The EPA landing team will be held by Patrice Simms of Earthjustice, an environmental lawyer who began his career at EPA and served in the Obama administration as a deputy assistant attorney general in the Environment and Natural Resources Division at the Justice Department. Also on the team are Cynthia Giles, who served as EPA’s top official for compliance and enforcement under Obama, and Ken Kopocis, its top chief for water quality.

The Interior team includes Maggie Thomas, who was a climate adviser to the Democratic presidential campaigns of Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, both of whom proposed ending Interior’s oil, gas and coal leasing. It also includes Kate Kelly, director of the Center for American Progress’ public lands program; Elizabeth Klein, an Interior veteran close with David Hayes, the deputy secretary under the Clinton and Obama administrations; Kevin Washburn, who was assistant secretary for Indian Affairs; and Bob Anderson, an attorney specializing in Native American law who was co-lead of Obama’s Interior transition.

The Energy Department team is led by Arun Majumdar, the initial director of the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, which started under Obama. Also on that team is the AFLCIO’s Brad Markell, a strong advocate of carbon capture technology. The CEQ team is headed by Cecilia Martinez, the environmental justice advocate who was a member of the Biden campaign’s climate engagement advisory council. She’ll be joined by Nikki Buffa, who was deputy chief of staff at Obama’s Interior, and Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Shara Mohtadi, who helped lead America’s Pledge and the group’s anti-coal work.

The Department of Justice team includes Richard Lazarus, a Harvard University professor who worked on the landmark Massachusetts v. EPA Supreme Court case, which in 2007 established EPA’s obligation to regulate greenhouse gas emissions under the Clean Air Act.Earlier this year he published a book called “The Rule of Five” about the people and issues that shaped that case (Greenwire, Sept. 14).

Sue Biniaz, the State Department’s top attorney on climate change under four presidents, is a member of State’s landing team. She’s credited with saving the Paris Agreement at least twice by supplying diplomatic words in late-night scrums at climate conferences. That helped the U.S. negotiating team bring home a deal that wouldn’t require Senate ratification while satisfying other global players that the agreement would still have teeth. “Everybody always used to say that Sue knows where every comma is in the Paris Agreement,” said Nathaniel Keohane, senior vice president at the Environmental Defense Fund and a veteran of Obama’s White House.

The Treasury team includes Andy Green, now of the Center for American Progress, who worked on pricing climate risk as a lawyer for the Securities and Exchange Commission. Another Treasury transition official is Marisa Lago, who handled climate finance under the Obama administration and oversaw adaptation projects as chair of the New York City Planning Commission.

The Department of Transportation team includes Patty Monahan, a member of the California Energy Commission and a vocal advocate of electric vehicles, as well as Austin Brown, who was assistant director for clean energy and transportation in Obama’s Office of Science and Technology Policy.

The team for the General Services Administration—which oversees federal procurement and will figure heavily into Biden’s plan to de carbonize the government—includes Josh Sawislak, a former CEQ official who is now a senior adviser to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions.

The Defense Department team includes Sharon Burke, the former DOD assistant secretary who has focused on climate change’s impact on the military.

The Department of Homeland Security team includes Craig Fugate, the Obama administration’s Federal Emergency Management Agency director.

The team for the Federal Reserve includes Amanda Fischer, a vocal advocate of the Fed accounting for climate risk and a former chief of staff to progressive Rep. Katie Porter (DCalif.)- The transition team for the United Nations includes Leonardo Martinez-Diaz, global director of the World Resources Institute’s sustainable finance center. He was formerly the Treasury Department’s deputy assistant secretary for energy and environment. And the National Security Council team is headed by Jeff Prescott, who published an oped last year comparing Trump’s climate denial to the administrative failures that led to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Reporters Maxine Joselow, Thomas Frank, Avery Ellfeldt and Benjamin Storrow contributed

Decarbonizing the buildings and construction sector is critical to achieve the Paris Agreement commitment and the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Developments Goals (SDGs): responsible for almost 40% of energy- and process-related emissions, taking climate action in buildings and construction is among the most cost-effective. Yet, this 2019 Global Status Report on buildings and construction tells us that the sector is not on track with the level of climate action necessary. On the contrary, final energy demand in buildings in 2018 rose 1% from 2017, and 7% from 2010.

These findings stand in stark contrast with the 2019 Emissions Gap Report, which states that we will have to cut almost 8% of emissions each year from 2020, and are confirmed by the International Energy Agency (IEA) World Energy Outlook 2019, which found that in 2018 the rate of improvement in energy intensity had slowed to 1.2% – less than half the average rate since 2010. Both reports underline the need for urgent action by policy makers and investors. To meet the SDGs and the IEA Sustainable Development Scenario, we need to reverse the trend and make a concerted effort to de-carbonize and enhance energy efficiency in buildings at a rate of 3% a year.

In 2020, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement are due for revision – an opportunity that cannot be missed to ramp up ambition in the buildings and construction sector. The 2018 Global Status Report on buildings and construction found that a total of 136 countries have mentioned buildings in their NDCs, yet few have specified the actions they will use to reduce emissions. Therefore, in their new NDCs, nations must prioritize actions to decarbonise this essential sector. This means switching to renewable energy sources. It means improving building design. It means being more efficient in heating, cooling, ventilation, appliances and equipment. It means using nature-based solutions and approaches that look at buildings within their ecosystem, the city.

The report also tells us that the building stock is set to double by 2050, which presents another important opportunity not to be missed. In making good on SDG 11 with its provision for affordable and adequate housing for all, we need to make sure we promote clean solutions and innovations to make buildings future-proof. In line with SDG 7, we have to double our efforts on energy efficiency to bring gains of at least 3% per year.

Such efforts must be supported through investments in energy efficiency; but here also, the numbers show that we are headed in the wrong direction: investment in buildings sector energy efficiency flattened in 2018 instead of showing the growth needed. In September, at the UN Secretary General’s Climate Summit, countries as well as the private sector made commitments to a zero-carbon buildings sector, and the goal of mobilizing USD 1 trillion in “Paris-compliant” building investments in developing countries by 2030 was set. At the same time, the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance was founded with the world’s largest pension funds and insurers – responsible for directing more than USD 2.4 trillion in investments – committed to carbon-neutral investment portfolios by 2050.

These are signs of hope. And change is in the works. This report provides examples of country, city and private sector actions, of how the buildings and construction sector is reforming. Through this Global Status Report series, we are keeping an eye on progress made. And through another joint product – a series of regional roadmaps – we are working with experts and policy makers in defining their re

It is well within the realm of possibility for the buildings and construction sector to deliver its full mitigation potential and help the world achieve its climate and sustainable development goals. Together, we can build for the future.

Executive Summary

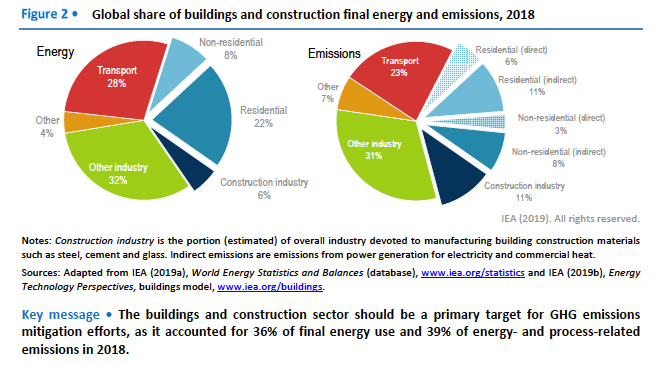

The buildings and construction sector accounted for 36% of final energy use and 39% of energy and process-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2018, 11% of which resulted from manufacturing building materials and products such as steel, cement and glass. This year’s Global Status Report provides an update on drivers of CO2 emissions and energy demand globally since 2017, along with examples of policies, technologies and investments that support low-carbon building stocks. The key global buildings sector trends are:

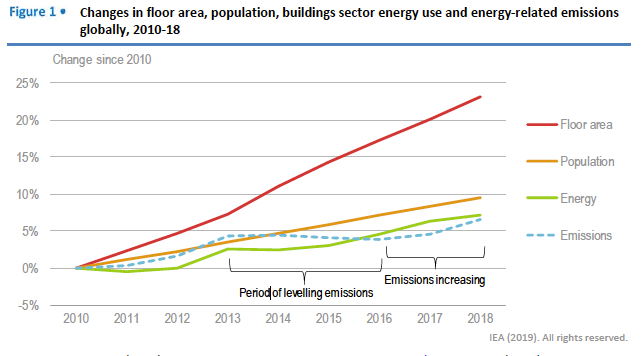

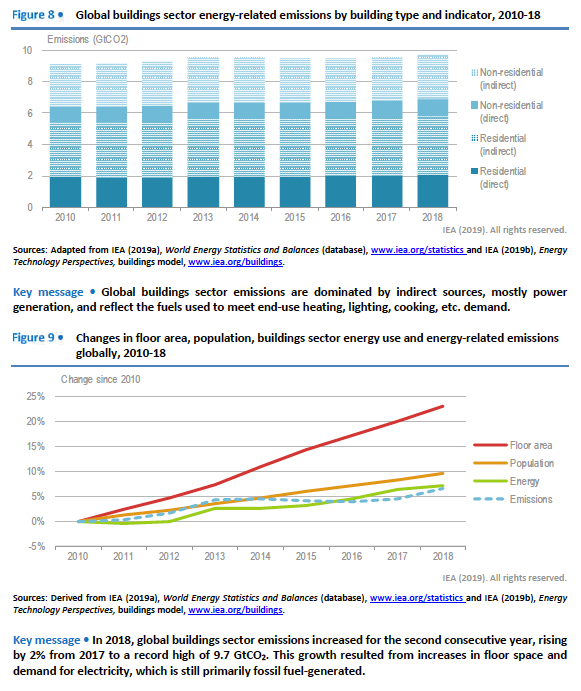

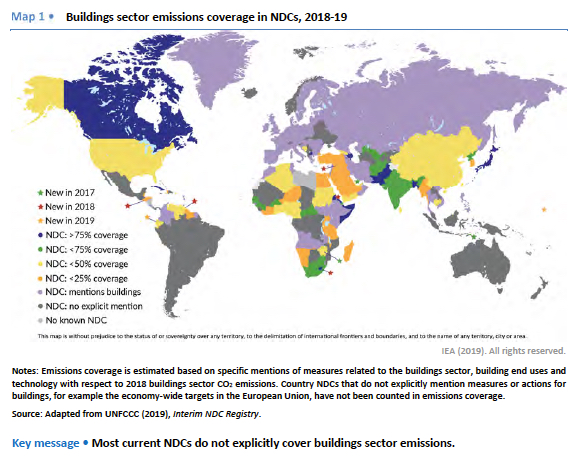

In 2018, global emissions from buildings increased 2% for the second consecutive year to 9.7 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2), suggesting a change in the trend from 2013 to 2016, when emissions had been leveling off. Growth was driven by strong floor space and population expansions that led to a 1% increase in energy consumption to around 125 exajoules (EJ), or 36% of global energy use.

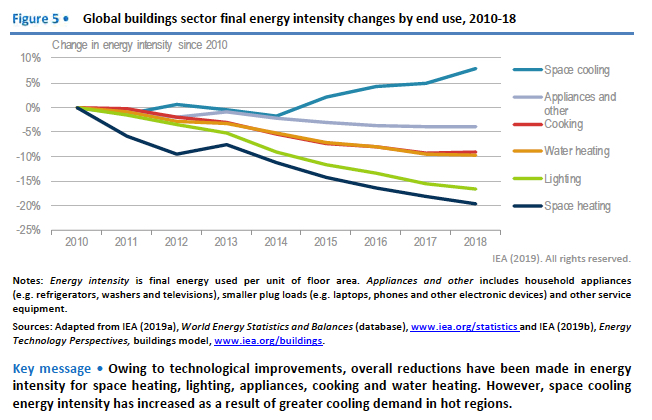

A major source of rising energy use and emissions by the global building stock is electricity, the use of which has increased more than 19% since 2010, generated mainly from coal and natural gas. This indicates how crucial it is to make clean and renewable sources of energy accessible, and to use passive and low-energy designs more widely in building construction. From 2017 to 2018, energy intensity continued to improve for space heating (-2%) and lighting (-1.4%), but increased for space cooling (+2.7%) and remained steady for water heating, cooking and appliances. At an 8% increase in 2018, space cooling became the fastest-growing use of energy in buildings since 2010, though it accounted for only a small portion of total demand at 6%.

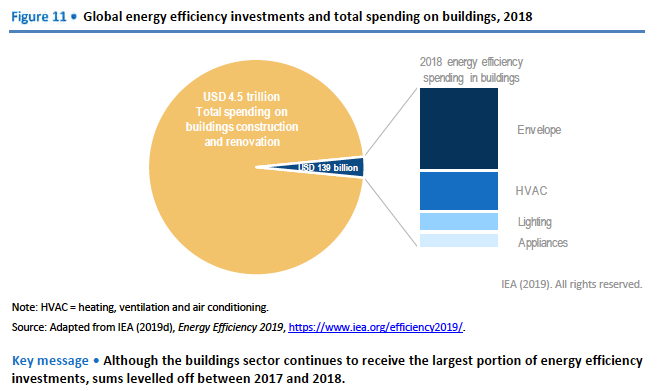

As part of their plans to limit greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, 184 countries have contributed NDCs under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Although most countries (136) mention buildings in their NDCs, few detail explicit actions to address emissions within the buildings sector. In the next round of NDCs, covering 2020 to 2025, further focus is needed on actions to mitigate building emissions through switching to low-carbon and renewable energy sources, and greater attention should be paid to low-carbon building materials, building envelope improvements, nature-based solutions, and equipment and system efficiency. These efforts will require higher investments than the USD 139 billion of 2018 – which was a 2% drop from the previous year. To tackle emissions and reduce energy intensities in the buildings and construction sector, governments, companies and private citizens must raise investments in efficiency adequately to offset growth.

Although greater ambition is needed, policy makers, designers, builders and other participants in the buildings and construction value chain globally are undertaking activities to de-carbonize the global building stock and improve its energy performance.

These activities to enact regulations and enable greater market adoption of low-energy buildings are encouraging signs of efforts to curb future energy demand and emissions. Some countries have also established strategies to work towards achieving a net-zero-carbon building stock by 2050 or earlier. For example, Japan and Canada are developing new policies to achieve net-zero and net-zero-ready standards for buildings by 2030. As more countries prepare their NDCs, more ambitious strategies to address existing building stocks will be put forward.

The Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction (GlobalABC) and the International Energy Agency (IEA), in collaboration with regional members and stakeholders, are developing Regional Roadmaps for Latin America, Africa and Asia to forge pathways towards efficient and resilient zero-emissions buildings and construction sectors. The roadmaps:

Support activities such as national alliances that unite local construction value chains to enable the development and implementation of national strategies for zero-net-energy and-emissions buildings.

The buildings and construction sector globally is showing an increase in both emissions and energy use, limited progress on new and existing policies, and a further slowdown in energy-efficiency investment growth. More action is therefore needed to curb emissions and deliver a low-carbon, sustainable built environment.

Building construction and operations accounted for the largest share of both global final energy use (36%) and energy-related CO2 emissions (39%) in 2018 (Figure 2).

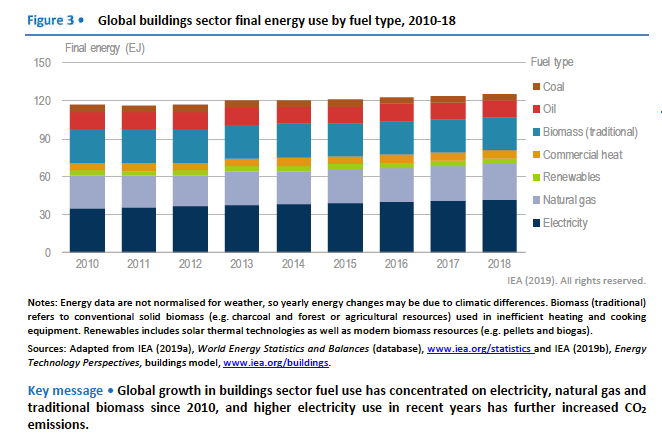

Global final energy consumption in buildings in 2018 increased 1% from 2017, and by more than 8 EJ (about 7%) since 2010 (Figure 3). While strong growth in the main buildings sector resulted from floor space and population expansion outpacing energy efficiency gains, floor area growth continues to decouple from energy demand, with floor area in 2018 having increased 3% from 2017 and 23% since 2010.

From 2010 to 2018, global electricity use in buildings rose by over 6.5 EJ, or 19%. Emissions, which result from the fuel sources used for electricity generation and still include high levels of coal, especially in emerging economies, also rose in 2018. Continued de-carbonization of the electricity supply is therefore needed to transition to clean-energy, low-carbon buildings. Also during 2010-18, renewable energy became the fastest-growing energy source for buildings, with its use

increasing 21% (up 3% during 2017-18 alone). Natural gas use rose 8% during the same period, meeting new demand as well as displacing coal use, which dropped by almost 10% globally during 2010-18 (-2% from 2017 to 2018).

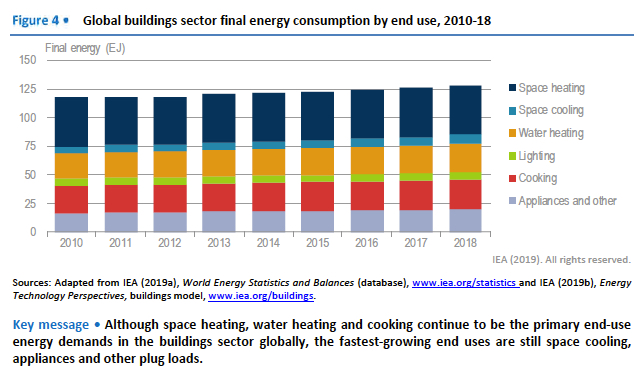

Globally, greater end-use energy consumption due to significantly higher electricity use since 2010 for space cooling, appliances and hot water, is resulting in increased emissions (Figures 4 and 5). Space cooling demand rose more than 33% during 2010-18 and by 5% in 2017-18, while energy demand for appliances in 2018 increased by 18% since 2010 and for water heating by 11%. At the same time, space heating demand decreased 1% from 2010, though it has remained

stable for the past five years at one-third of total global energy demand in buildings.

From 2010 to 2018, changes in buildings sector energy intensity per unit of floor area (as a proxy for energy efficiency) show that the greatest improvements (i.e. reductions) were in global average space heating (-20%) and lighting (-17%) (Figure 5). Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) continue to be important in reducing energy consumption for lighting as floor area increases and falling consumption for space heating indicates that building envelopes have improved. However, as floor area has been expanding rapidly in hot countries, cooling demand is increasing. As better building envelopes are crucial to reduce energy use for heating and cooling, building codes must remain a policy priority along with technology efficiency improvements.

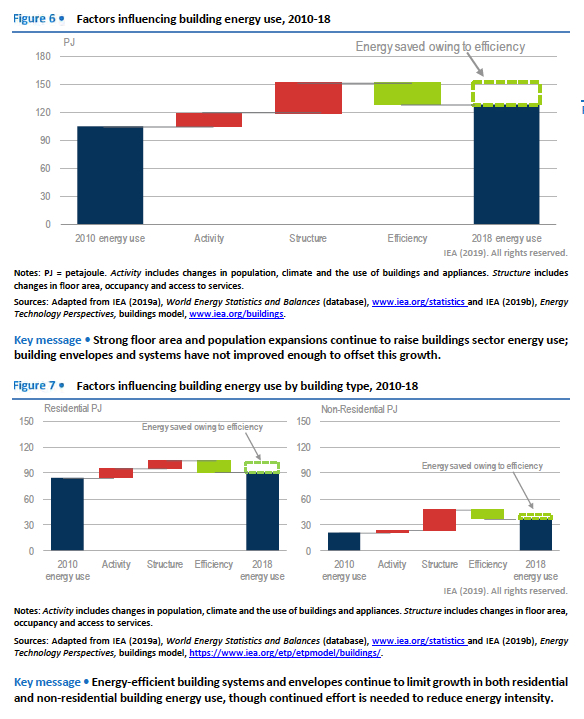

Factors influencing global buildings sector energy use include changes in population, floor area, energy service demand (e.g. more household appliances and cooling equipment), variations in climate and how buildings are constructed and used. Those that have contributed most to higher energy demand since 2010 are floor area, population and building use, while improvements in building envelopes (e.g. better insulation and windows) and in the performance of building

energy systems (e.g. heating, cooling and ventilation) and components (e.g. cooking equipment) have helped to offset energy demand growth (Figure 6). Nevertheless, total energy demand in buildings continues to increase and greater investments in efficiency and passive design strategies are needed to limit demand and reduce energy intensity.

Final energy consumption in residential buildings made up more than 70% of the global total in 2018, with growth resulting primarily from floor area and population increases, while floor area alone remains the main driver of higher consumption in non-residential buildings (Figure 7). Consumption in residential buildings rose more than 5 EJ during 2010-18, and 3 EJ in non-residential buildings. Growth in residential demand continues to reflect population and floor area increases as well as development in emerging economies, along with a continued shift away from the traditional use of biomass towards modern fuels (e.g. electricity, liquefied petroleum gas and natural gas).

In a reversal of the previous five years, buildings sector emissions appear to have risen to 9.7 GtCO2 in 2018 – an increase of 2% since 2017, and 7% higher than in 2010. Buildings represent 28% of global energy-related CO2 emissions (39% when construction industry emissions are included). Indirect emissions (i.e. from power generation for electricity and commercial heat) account for the largest share of energy-related CO2 emissions in the buildings sector, representing around 68% of total buildings-related emissions from energy consumption in 2018 (Figures 8 and 9). The increases in emissions in 2016 and 2017 correspond with floor area and population expansions as well as growth in electricity demand (i.e. indirect emissions). Building construction emissions – those related to the manufacturing of building materials – amounted to a further 11 GtCO2 in 2018, for a total of 39% of global energy-related emissions.

By 2020, countries are requested to communicate their new or updated nationally determined contributions (NDCs) setting out their efforts to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. 2020 is therefore a key year for countries to enhance their NDCs and commit to more aspirational targets. In addition to NDCs, the coverage and strength of energy performance building codes and certification policies have continued to expand, and in 2018 several countries with updated codes adopted meaningful improvements that should reduce buildings sector energy demand growth, especially for heating and cooling, and make buildings and construction more sustainable.

Reporting on NDCs is an international process during which countries announce their national-level commitments to reduce emissions to limit the rise in average global temperature to less than two degrees Celsius (°C) above pre-industrial levels by 2100, as set out in the Paris Agreement. The 24th Conference of the Parties (COP24) in Katowice, Poland, presented the Katowice Climate Package that sets out the procedures and mechanisms to operationalize the Paris Agreement.

Within the package is guidance on communicating efforts to adapt to climate impacts; a transparency framework for efforts on climate change; a process for conducting a global stock take of overall progress towards the aims of the Paris Agreement; and directions for assessing progress on technology development and transfer. The package also contains directions for a further round of NDCs to be submitted by 2025.

To ensure comparability across all NDCs, it outlines how to develop mitigation goals and activities, specifically covering:

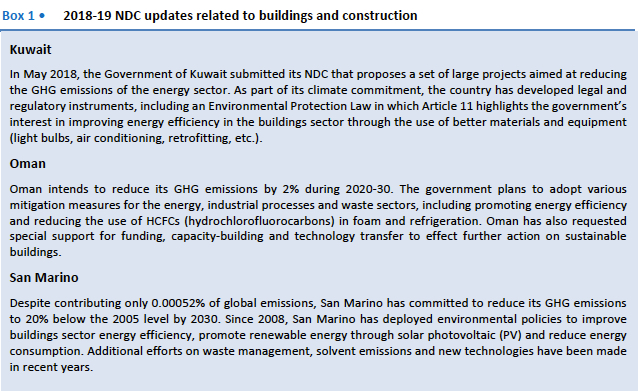

To date, most countries (184) and the European Union have submitted NDCs, and many countries (136) mention buildings, although most NDCs still do not include explicit actions to address buildings sector energy use and emissions (Map 1). Seven countries updated their NDCs in 2018-19, and the Marshall Islands submitted their second NDC in 2019.

To help countries address buildings-related emissions, GlobalABC has developed guidance on how to include buildings in the NDCs through mapping, prioritizing, implementing and monitoring (UNEP, 2018). GlobalABC supports ambitious buildings sector climate actions, defined as those that will move the sector towards zero emissions by 2050 while increasing the built environment’s resilience and adaptive capacity.

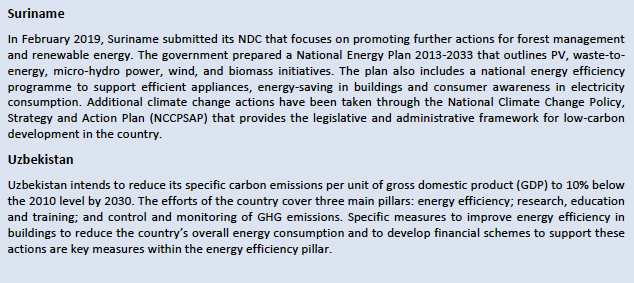

NDCs submitted in 2018-19 focus on improving building performance codes and standards, fuel conservation and phasing out inefficient products and equipment (Box 1).

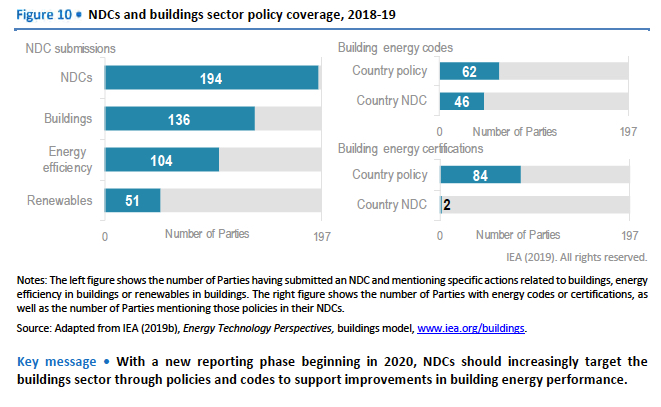

Of the 136 NDCs that now reference the buildings sector, most do not have specific targets or policy actions (Figure 10). While existing policies and NDCs covered more than 50% of buildings related CO2 emissions as of 2018,1 if committed NDCs were to become policy, the coverage would increase to more than 60%.

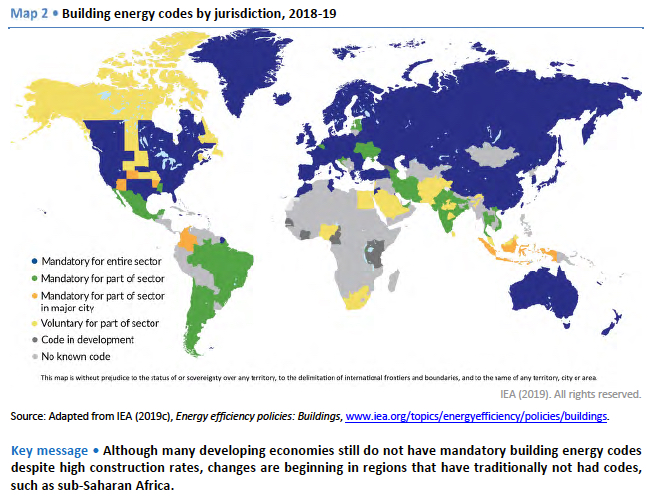

Building energy codes, or standards, are requirements set by a jurisdiction (national or sub-national) that focus on reducing the amount of energy used for a specific end use or building component. In 2018, 73 countries had mandatory or voluntary building energy codes or were developing them.

Building energy codes play an important role in setting standards for building construction that will reduce the long-term energy demands of the buildings sector. With mandatory and progressive codes, energy use can be better managed as floor space expands, and progressive codes can respond to changes in legislation and the availability of cost-effective technologies. For maximum impact, it is essential that a building code be strong, be improved progressively over time and be implemented effectively. It is also advisable to move towards mandatory codes for both residential and non-residential buildings.

Of the 73 countries with codes, 41 have mandatory residential building codes and 51 have mandatory non-residential codes; 4 have voluntary residential codes while 12 have voluntary non-residential codes; and 8 more are in the process of developing building codes. Greater coverage, adoption and strength are needed to continue improving the energy performance of new buildings and major refurbishments.

There is still considerable need for countries and sub-national jurisdictions to develop and effectively implement building energy codes to reduce future energy demand and avoid expensive retrofits later. There are signs, however, that such codes are being considered by a number of countries in central Africa and Central America.

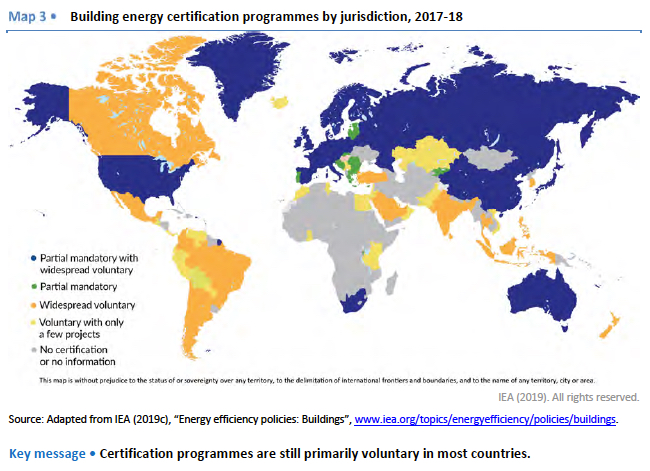

Building energy certification involves programs and policies that evaluate the performance of a building and its energy service systems. Certification may focus on rating a building’s operational or expected (notional) energy use, and can be voluntary or mandatory for all or part of a particular buildings sector. The aim of energy performance certification for buildings is to provide information to consumers about their buildings and to gradually create a market for more efficient buildings.

As of 2018, 85 countries had adopted building energy performance certification programs(Map 3), and several countries and sub-national jurisdictions also updated their building energy certification policies in 2017-18 (see Box 3). The use of certification programs is growing, with voluntary certification for high-end buildings becoming a popular means of adding value, but there is still a lack of large-scale adoption of full, mandatory certification programs outside the European

Union and Australia. This means that tracking building energy performance over time and subsequently disclosing the information is still limited.

Total energy efficiency spending2 on buildings amounted to USD 139 billion in 2018 (Figure 11), a decline of 2% from 2017 (IEA, 2019). Driving this deceleration is the slowdown in investment within the European Union, even though the United States and China continue to invest in more energy efficient building systems. Within Europe, governments have either limited investment expansions (e.g. the United Kingdom and France) or have cut it back (e.g. Germany). In China, by comparison, overall real estate investment has grown 6% per year since 2015 to over USD 1.8 trillion in 2018. Chinese investment has been focused largely on residential buildings, with investments in efficiency rising to USD 27 billion in 2018 – a 33% increase from 2015. In the United States, investments in both residential and non-residential construction grew at a rate of 3.8% from 2015 to 2018, to reach USD 1.4 trillion, but the share of investment for improving building energy efficiency is in decline at 2% of total 2018 investment. The real estate market continues to embrace and invest in green buildings and green-building rating systems, with their overall Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) scores increasing, which is a promising sign for the sector (GRESB, 2019). The 2018 Global Status Report (IEA and UNEP, 2018) provides further details on past investment and financing in sustainable buildings.

The overall investment trend mirrors slower progress for energy efficiency outcomes, with 2018 marking the third consecutive year in which the energy efficiency improvement rate slowed. An underlying factor was the static energy efficiency policy environment in 2018, with little progress made in implementing new efficiency policies or increasing the stringency of existing ones.

In the summer of 2019, an online questionnaire was sent to all GlobalABC members requesting their input for the 2019 Global Status Report, as well as case studies. The questionnaire provided members the opportunity to highlight their activities in support of low energy and low-carbon buildings and cities through actions such as new or improved building codes and standards, building certifications and NDCs. The following sections present insights from the responses.

The survey received 43 responses from a mixture of civil society organisations (30%), national governments (28%), the private sector (21%), non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (7%) and others. Although the majority of countries noted that no updates had been made to their NDCs in 2017 or 2018, several had updated their commitments relating to strategies for 2050 on buildings and construction (see Box 4) and most that responded had begun the 2020 revisions process.

A number of countries identified financing schemes to facilitate investment in low-emissions buildings through forms of green financing, for example a state grant in Sweden to support low rent apartments, whereby a higher grant can be received if the building’s energy performance surpasses the building code. In Senegal, local governments are offering reduced taxes on development when local materials are used in housing construction.

In 2018 and 2019, building energy codes were updated in three respondent countries: Colombia, Japan and Senegal. For Colombia, this involved revision of its mandatory local and regional building energy codes for both residential and non-residential buildings, covering public and transport spaces for the first time. Japan’s revisions included an update to the national partially mandatory energy code for both residential and non-residential buildings.

Several countries are considering innovative building codes or expanding existing ones to cover broader lifecycle emissions beyond energy. For example, Sweden is investigating addressing the environmental impact of new buildings by using an environmental certification. Currently in the process of revising its CO2 Act, Switzerland is considering introducing a very strict CO2 emissions cap for existing buildings, which in most cases would result in the banning of fossil fuel-based

heating systems unless the building is very well insulated. Meanwhile, Canada’s codes seek to leverage high-performance technologies and construction practices that are at the commercialization stage, and to include more climate change adaptation and resilience measures.

Building energy performance certification remains largely voluntary among respondent countries, with some exceptions for certain building types (commercial buildings in Tokyo, New York and Singapore, for example) or locations (e.g. both residential and non-residential buildings in the European Union). A range of certification types are being used around the world to indicate performance, and they are a mix of predicted and measured approaches. Respondents that

recently updated their certifications include Sweden (2018), which has included mandatory overage for all building types, and Medellin, Colombia (2019), which updated its voluntary coverage for residential and commercial buildings.

A global transformation to a highly energy-efficient and low-carbon buildings and construction sector is essential to realize global ambitions to limit the rise in average global temperature to less than 2°C above pre-industrial levels by 2030. The critical window of opportunity to address buildings and construction emissions is in the coming decade, to avoid locking in inefficient buildings for decades to come. There is an equally critical need to address energy performance improvements

and emissions reductions in the world’s existing building stock.

The following section outlines the key priority areas identified in GlobalABC’s 2016 Global Roadmap (UNEP and GlobalABC, 2016) as well as the actions necessary to deliver a zero-carbon global building stock.

Future GlobalABC work includes developing regional roadmaps to provide targets that are more country- and region-specific. For further information on best practices and examples of existing policies and technologies for the buildings sector, see www.iea.org/buildings. Updates on Global Roadmap activities

GlobalABC roadmaps focus on developing a collaborative approach across eight thematic areas necessary to create a sustainable built environment for the future. Efforts exemplifying roadmap ideas are being made in countries and cities all around the world, and this section highlights numerous country-level case studies across various themes as examples of these activities (Box 5).

Urban planning policies should be used to reduce energy demand, increase renewable energy capacity and improve infrastructure resilience. Globally, local jurisdictions have significant control over how energy is used, and the emissions created by transportation, building construction and

lifetime building operations can be regulated through urban planning. Urban planning can also help combat climate risks by ensuring building resilience. Key actions in the area of urban planning include:

There needs to be a higher uptake of net-zero-operating-emissions buildings. With the global population increasing by 2.5 billion by 2050, new buildings will have an important effect on future buildings-related energy use and emissions. Several key policy, investment and design actions can achieve sustainable (low-emissions, efficient and resilient) new buildings:

The rate of energy renovations and the level of energy efficiency in existing buildings need to be increased. Key steps to raise the performance of existing buildings involve increasing both the number of buildings improved and the amount of improvement achieved.

Better energy management tools and operational capacity-building can reduce the amount of operating energy needed and, hence, emissions. While delivering efficient and resilient low emissions new or renovated buildings is essential, it is equally important to manage existing buildings efficiently. Key actions to improve the energy management of buildings include:

It is important to reduce energy demand from systems, appliances, lighting and cooking. Energy consuming lighting, appliances and equipment systems, which commonly have a shorter lifetime than the buildings they are in, offer a significant opportunity to reduce emissions in new and existing buildings. Key actions to increase system sustainability in buildings include:

Taking a lifecycle approach can reduce the environmental impact of materials and equipment in the buildings and construction value chain. Key actions to increase the sustainability of building materials and products include:

Building risks related to climate change can be reduced by adapting building designs and improving resilience. Key actions to increase the resilience of buildings include:

Increasing access to secure, affordable and sustainable energy can reduce the carbon footprint of energy demand in buildings. Key actions to support the clean energy transition in buildings include:

GlobalABC aims to bring together all elements of the buildings and construction industry as well as countries and stakeholders to raise awareness and facilitate the global transition to low-emissions, energy-efficient buildings. GlobalABC works on a voluntary collaboration basis in five working areas in which members are invited to take part.

Work Area 1: Awareness and Education

The purpose of this area is to support capacity-building to promote the transition to a resilient, efficient and zero-emissions built environment and to raise awareness of the sector’s transformation potential, convey a sense of urgency, develop common narratives, and formulate key messages. It aims to disseminate new approaches and solutions, share best practices through the new GlobalABC website, establish an interactive knowledge database to enhance peer learning, and provide training and education through webinars and online courses.

Work Area 2: Public Policies

This area attempts to unite the numerous independent and scattered building and construction sector stakeholders – particularly public authorities – through effective regulations and norms as well as financial and fiscal incentives. It also aims to support the development of national alliances, promote the integration of sustainable building objectives into NDCs, and enable city and sub-national engagement. A local government public policies group has been created to identify opportunities, facilitate community-level climate and energy strategies and promote co‑ operation among national and sub-national governments. Another sub-group focuses on adaptation and is developing a report to be released in 2020 on how the building industry is readjusting.

Work Area 3: Market Transformation

This area is designed to engage businesses and other stakeholders in de-carbonizing the entire buildings sector value chain, fostering multiple partnerships and a common culture among private and public sector participants to facilitate market transformation. This involves defining voluntary arrangements to prepare regulations and enable innovation in the market. It also include developing guidance on science-based targets that can be used to help transform the buildings and

construction sector by identifying a common metric and language for all companies to use through the Science-Based Targets for Buildings (SBT4buildings) project led by the World Business Council or Sustainable Development (WBCSD).

Work Area 4: Financing

This area is working to narrow the public and private financing gap for investing in efficient and resilient zero-emission buildings and construction, including property development. It is also helping draw attention to the sector’s financing needs, mapping existing financing opportunities,promoting innovative financing tools, enabling the flow of reliable information for investors, and informing public bodies of the budgeting and funding policies needed to conceive and implement

energy efficiency measures in buildings. For example, the International Partnership for Energy Efficiency Cooperation (IPEEC) and the Japanese government organized the G20 Global Summit on Financing Energy Efficiency, Innovation and Clean Technology, recognizing in its final Tokyo Declaration how important it is for the real estate and buildings sector to begin shifting financing towards energy efficiency.

Work area 5: Measurement, Data and Information

The purpose of this work area is to elaborate a fair and harmonized measurement system to close the information gap and thereby support buildings and construction sector policies and investments with measurable, reportable and verifiable data. Key barriers, however, relate to information availability, collection, quality, reporting, storage and accessibility. To overcome these obstacles, the work area team is coordinating an industry-wide global effort to develop a digital

building data and information collection tool, known as a “building passport”, to promote greater cross-sectoral data transparency and consistency and information exchange. All work areas welcome new participants. Please contact global.abc@un.org for more information.

Launched at COP21, GlobalABC is a voluntary partnership of national and local governments, intergovernmental organizations, businesses, associations, networks and think thanks committed to a common vision: an efficient and resilient zero-emissions buildings and construction sector. GlobalABC functions as an umbrella or meta-platform – a network of networks – that brings together initiatives and participants focused on the buildings and construction sector. The GlobalABC network currently has 128 members, among which are 29 countries (Map 4), and it welcomes new members interested in contributing to the global transition to a low-carbon, energy-efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector.

The French and German governments jointly initiated the Program for Energy Efficiency in Buildings (PEEB) at the end of 2016 at COP22, and the program was catalyzed by GlobalABC. PEEB supports implementation of the Global Roadmap: Towards Low-GHG and Resilient Buildings in its first partner countries: Mexico, Morocco, Senegal, Tunisia and Viet Nam. PEEB is a partnership program implemented by the Agence Française de Dévelopment, Deutsche Gesellschaft für

Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH and the Agence de l’Environnement et de la Maîtrise de l’Énergie (ADEME). PEEB has identified EUR 600 million worth of energy-efficient building projects and has already committed EUR 160 million.

Action at the national level is needed to work towards an efficient and resilient zero-emissions buildings sector, and national alliances are ideal to help various professions connect and exchange information, and to make the topic more visible in national policy debates. Alliances can be organized by the public or private sector as either volunteer-based or formalized structures. National alliances offer recommendations for policy makers and actively work to enhance economic activity. Typical pursuits range from awareness-raising, training sessions and project assistance to legislative lobbying.

National alliances have been successfully established in France, Germany, Mexico, Morocco and Tunisia, in many cases inspired by GlobalABC. Forming bridges among various sectors and industries, these alliances bring together leading representatives of public, private and civil society institutions for the creation of a sustainable buildings sector:

PEEB currently supports the national alliances in Mexico (ALENER) and Morocco (AMBC) with awareness-raising activities as well as capacity-building and training for their members. Most recently, expert working groups discussed the topic of buildings according to the five GlobalABC working areas during the relaunch of the Mexican national alliance in September.